A Few years ago I started making drawings of animals and foliage. Often, the creatures are out of place: meerkats in an underwater world, whales swimming among trees with birds flying by, ocean turtles navigating Spanish moss. I use a range of materials, both color and black and white, and things change in scale. I had, and continue to have, fun with them because I make them in only a few days—I have an idea, I make it, and I can see if it worked visually or not, and be on to the next one. I also really like that they are all about the same size. They fit in a portable portfolio, and now I have a collection of them, even though quite a few have been sold. It wasn’t long after I started making them that I started calling them “sketches for murals,” and many of them have felt like that; that they could be four stories tall, instead of 15”. From the beginning, this project in Cataño was exciting to me because it allowed me the opportunity to realize that, to take some new sketches for murals, and make them into murals; to actually have a forty-foot manatee swimming through the sky, or a large duck swimming next to a tiny ferry on a wall. It has been an exciting opportunity, a great chance to make something that I have wanted to make, and to make it in a beautiful location, with the input of many people from all around the area. It has been a great opportunity.

When I was first approached about painting the murals on the Cataño pyramid, I was both excited by the prospect, and intimidated. I had done some public artwork on a large scale; most closely I had facilitated and organized the production of four murals with youth and community groups, in Medellín, Santa Fe and San Juan. And more visibly I had designed and developed a large ceiling mural for the Martinez Nadal Station of the Tren Urbano in San Jun. This piece is 42 feet in diameter, but I actually had not fabricated it. It had been made from esmalte, small handmade glass tiles, by Stephen Miotto and Travisanutto Mosaici, experts in the production of Byzantine mosaics. So, painting the whole Cataño pyramid was a new challenge, both in execution of the actual process.

I visited the pyramid, walked around it, took a photos. It is an old structure—forty or fifty years old—with no apparent function. A three to four story pyramid, built about twenty feet from the shore of San Juan Harbor, it has never had a stable function. It was once a library, which makes a bit of sense, as there are two schools across the street. Passersby would tell me that it had been a number of other things over the years, a nautical club, a restaurant, offices, but it had mostly been empty over the years. It was last repaired five or six years ago, apparently, but then Hurricane María came through and damaged the building considerably. It was ransacked a bit as well, stuff was stolen, and graffiti painted on the interior. My intervention would be the first step in making the pyramid one of the central features of a new sustainable ecological tourism initiative. This project is being developed by the Ana G. Mendez University, in close collaboration with the two large nature reserves in the town of Cataño, and in constant consultation with community leaders from the several large neighborhoods in Cataño.

It made sense then that the university and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Puerto Rico, their partner in coordinating the artwork that would be part of this new project, invited me to participate in four workshops with community leaders. The workshops were held digitally, as we were under the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. I prepared some material for each meeting; I presented a brief overview of my artwork, an overview of my favorite artists; and we had two meeting focused on the built environment of Cataño, and the natural context of the city. The last two meetings focused much more on the leaders’ participation, although all of these meetings were designed to hear their input more than lecturing them on anything.

It took a few minutes to loosen people up, and then everybody had stories to tell about their town, about their memories and perceptions of animals and plants in their surroundings. One story was that there used to be so many crabs that residents had to sleep under mosquito netting to keep the crabs about of their beds. Another spoke about the enormous kaleidoscopes of butterflies that used to sweep over the area. Many mentioned the typical duck, known as a chirriria, that lives in the wetlands of this coastal city. And the discussion turned to the marine life in the harbor, fish, manatees and dolphins, as well as water birds, cranes and pelicans, that are common all along the shore. When I asked about mammals, there was a discussion of the horses that are kept all over the city, often in the poorer neighborhoods, and the bats that fly through around sunset—one of the biologists from the UAGM (the university) clarified that those bats actually live in Guaynabo, in the mogotes (karst formations) and they fly down to the shore every day, as they are fishing bats.

When we spoke about the buildings in the city, there was discussion of the few fancier buildings and the two modernist churches designed by Henry Klumb, as well as a discussion of the way their neighborhoods had bettered themselves, had helped create canals to carry the water to the bay. I have to admit that I was struck by the name of one of the two major waterways of the city, Caño la Malaria, and the way it evoked what must have been terrible times decades ago. Cataño is a physically small city, squeezed in between Guaynabo and the water. The city inevitably looks out over the water, and towards Old San Juan, and its history is largely tied to commerce across the bay, as the terminal for many goods from the island that were then ferried to San Juan and its port on the other side of the harbor.

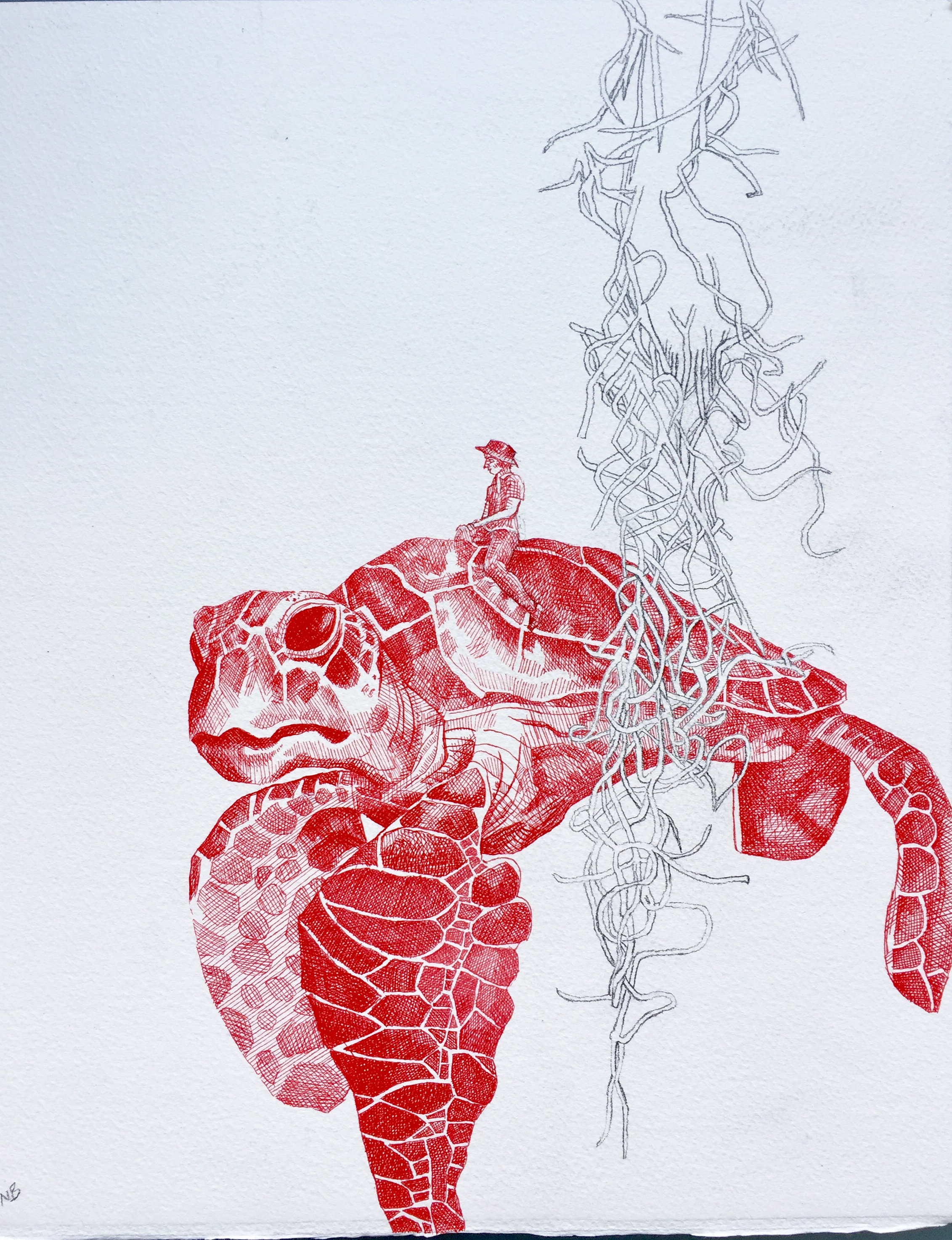

I took this information and started working on sketches. There were initial small pencil sketches in my handy sketchbook—some just doodles, others a bit more developed, and then a few that focused on specific animals or trees. Then I worked on more finished drawings—not drawings for the pyramid precisely, but careful drawings of some of the elements, executed in pencil and ink: a drawing of cranes and tigers, with a small astronaut in the middle; a careful pencil drawing of a mangrove swamp viewed from a bridge in Hato Rey; a palm tree by the beach in Luquillo; five or six crabs rendered in blue ink, climbing among a few bears; and bats in a few drawings, and even in a large painting, cavorting with sharks. These drawings were independent, free-standing works, but also opportunities to integrate these images into my visual vocabulary. They culminated in four sketches, on large sheets of paper, about 3 feet by 3 feet, painted and drawn within a triangle. These were my designs for the pyramid. They integrated many images from the conversations, as well as my ideas, my design sensibility, my interest in making each side a unique piece, and also connecting them. I submitted the sketches to my coordinator at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Windy Cosme, and waited for reactions. That took a few weeks, mostly because there were a number of organizations involved in the project. The Museo and the Universidad Ana G. Mendez were the principal sponsors, and we had an exciting remote meeting, where the designs were approved with the recommendation that some images of the ferry be added; the ferry is a central part of Cataño’s history. I thought about that proposal and researched the history of the ferry, adding three ferries, from different periods over the last hundred years, to three of the sides. The designs were then shown to the mayor’s office. They took some time to get back to us, and suggested that the east side, which faces a parking lot with food trucks and looks towards the actual center of the town, had a boring design. I considered the observation and added a big red octopus. With these adjustments, the design was set.

We started work at night, in July. The crane or lift, or girafa, was there on loan, and a projector. I didn’t know how to manipulate the lift, so Alex from the museum took control, after he connected the projector to his car battery, with an adaptor, and we projected the design onto that side, the east side of the pyramid. We both went up in the cage, and I quickly marked the lines of each figure and each main element of the background. That’s how the basic scheme, and the proportions of the different parts, was set on the wall. Even working quickly, it took two or three hours to move the cage around the whole side and mark all of the different elements.

I was nervous up in the cage, 40 feet off the ground, and watching to try and figure out which control moved the cage in which direction. A that point we had only the house paint on hand—the ink and artist’s acrylic wouldn’t arrive for a few weeks due to supply chain issues. We started with the background, painting the blue area, the green area, and leaving the animals blank. My assistant, Migdalia Umpierre, was right with me, and it was hot all morning, from soon after the sun came up at 7 am—it was July in Puerto Rico.

We continued with the bottom layers and I was there early most days, for sunrise at 6 am. By 9 am, I was packing up to go to work (at my desk job), driven away by the searing sun as well. The acrylic paint arrived, Golden paint, and Windy and Alex were worried that it wouldn’t be enough; I was confident, even if I didn’t really know how much paint I’d need (I eventually used up the whole gallon of white and bought an additional bottle at a local art supply store). But first I mixed the colors to paint the butterflies: those orange, orange-red and yellow-orange forms that cross diagonally up the pyramid and appear on all four sides—but I was still working on the lower levels. We could reach the first eight feet or so from the portable scaffolding, and could also clamber up onto the overhang that goes all around the pyramid and paint everything up to about fifteen feet, right up under the main large panels. I spent a whole Saturday painting the body of the large duck—all in shades of gray—from that ledge, on my knees. By then, I had switched to acrylic paint for the creatures and plants, understanding that the better-quality material would conserve its color and resist the sun and spray from the harbor a little longer than the house paint.

I had never painted or drawn things at this scale, or used some of these materials in this way. What a thrill to paint that duck body—twenty feet by six feet—in five shades of gray, and then clamber down to the ground and see how it all fit together and looked just as good as it did on a small canvas. I painted the bats—hanging below the ledge on the south side and taking flight on the east side.

I painted the first big blue crab at ground level (or drew it). I was using the same ink, shellac-based, that I use on paper or canvas, without knowing how it would hold up outside on cement. From the beginning I knew I would need an acrylic sealant for the whole piece. I was using a thick watercolor brush to work with the same pattern of lines I usually developed with a fine-line quill pen on paper. The cross-hatched lines were effective at capturing the form, with the same character. But the first night it rained and an area of the drawing ran a bit. From then on, I was careful to always have a can of clear acrylic spray on hand and to seal each day’s work, if it was ink, as a provisional measure until we could seal the whole project in a few months.

We worked our way around the whole pyramid—painting the lower section, up to about 15 feet. Some days I was alone, some days Migdalia could make it, and worked alongside me. There was one food truck that was always there weekdays, and opened before I arrived, making breakfast and simple sandwiches. In the early morning workers would stop and get an egg sandwich and watch the sunrise over San Juan harbor. Many days I ended my short shift the same way, although by nine the sun was well up in the sky, the view was just as good.

Weekends, the breakfast truck didn’t open. I’d walk a block to the empanadilla shop run by el Gordo Malhablado (the Swearing Fat Man), which always has a line of clients waiting to purchase a chicken, steak, beef, or pizza empanadilla (fried turnover).

Finally, it was necessary to elevate—there was nothing more to be done on the lower levels. The lift was delivered, and I was coached briefly on how to both drive it and manipulate the controls that adjusted the cage. And then it was up to me, and pretty quickly, somewhat by trial and error, I learned how to move up and around and also extend the cage toward the wall as it receded toward the tip of the pyramid. I can still feel the shaking of the cage, jostled by the wind, and the way that scared me. I would try to plant one corner of the cage against the sloping wall for security and stability, and paint what I could reach, before relocating a bit lower, or a bit to the side. It was nerve-wracking as I painted the little duck, and the upper crab, and then it wasn’t. By the time I painted the palm tree, I felt natural and comfortable suspended in that cage thirty or forty feet up in the air.

The red paint hadn’t arrived; the red ink also hadn’t arrived. Something in the cosmos, or the supply chain during the pandemic, was holding back the reds; so I recessed, giving up the lift while we awaited delivery. A few weeks later both boxes arrived, and then we had to wait a few days to get a lift—they were all in use on other projects, until we could finally get back in the saddle. First the orange octopus, and then the real challenge of the giant red manatee, all cross-hatched in ink. Each day I could cover about ten square feet of that manatee, building up the form with red lines crossing one over the other, as I listened to music or podcasts high above the harbor.

Migdalia began coating the pyramid with sealant. A few other friends joined in for a morning or a day, wielding a roller: Anna Nicholson, Malik Veira. At times it seemed like the project would never end, like there’d always be one more task, even as the final stages of the project were being executed. A second coat of sealant, and a constant eye on the clouds crossing the sky to avoid downpours.

It had been a beautiful place to start a day’s work, arriving in that parking lot just as the sun as rising, looking across at Old San Juan. Birds were gliding above the pyramid, casting their shadows as they approached. People were exercising, running, or walking along the waterfront. Many signaled their approval with a thumbs up, some stopped to chat or argue with me. One woman talked to me about her daughter who was interested in art and ended up telling me her life’s story and how she had started her business. Another passerby questioned the accuracy of one of my ferries, he had lived his whole life there; I explained that I had worked from photos of the old ferries. A few days later, he came back to apologize, explaining that he had verified his memory, and that my image was right.

There are two schools just across from the pyramid, and classes started in August. Parents would pull up, dropping their kids off. There would be a bit of traffic, and then the kids would drift out to the park by the pyramid to joke and chat. A few times I used the bathroom at the school, after showing the guard my vaccination card.

I also got to know the owner and employees of the food truck that was closest to the pyramid, and on longer days, on the weekend, I bought a hamburger there. After a while they would ask me about my progress, or where I’d been if I hadn’t shown up for a few days. It was funny that the woman who tended the register in the foodtruck often hadn’t seen the other sides of the pyramid—she went directly from the truck to her car without looking at her surroundings, unless I commented on what I’d been working on.

When I finally finished, when the second coat of sealant had been applied to the whole structure, when the last details had been retouched, it was both a relief and a sadness; I no longer had an urgency to jump out of bed every morning in the dark—the usual hangover of an ambitious project.

It would be a few months before the project was officially inaugurated. In late January, the museum staff, all the related people from the UAGM, and a representative of the City of Cataño gathered next to the pyramid. Under a tent to protect us from the hot sun, several of us reflected on the process: Marianne Ramirez from the MAC, Carlos Padín Bibiloni and Carlos Morales Agrinzoni from the UAGM, a representative of the city of Cataño, and I, all spoke briefly. We visited an exhibit of student art at a nearby boxing stadium, and a group from Isabela played folk-flavored music. There was much enthusiasm for the project, and it officially began its life as a landmark, as a background for selfies, as part of a walking route along the shore, and hopefully as the future anchor of an ecotourist area connecting that shore to the nearby wetlands and wildlife reserves.